Note from the Publisher: Continuing the preparation for an upcoming interview with historian Anton Chaitkin below is the transcript of a video recording of a lecture by

and H. Graham Lowry. Despite the fact that the lecture was held almost 30 years ago, the content is highly relevant to the understanding of the origins and continuity of evil politics conducted by misanthropic, imperialist oligarchical “interests tied to misery, degradation and suffering for the masses” (Webster Tarpley). Given the brazenly open highjacking of “The Science” during the “pandemic”, it is more than a striking coincidence that similar tactics had been applied against humanist efforts and achievements following the Renaissance with attempts to block the implementation of Leibnizian scientific principles designed to develop the nations of the world.

“If one steps back to comprehend what most Americans understood from these events during the 1740s, then one comprehends why the American Revolution was indispensable. Without it and without the power of the United States as a constitutional republic, Western European civilization, as created by the Renaissance, would not have survived.”

— H. Graham Lowry

Transcript of Lecture given on February 18, 1996. Webster Tarpley:

… [Benjamin] Franklin served as the American ambassador to the court of Louis XVI in Paris. Franklin and his fellow envoys faced the task of organizing diplomatic, military, and financial support for the revolution. Because of their efforts, the British soon faced four belligerent powers, not one. as the Americans were joined by France, Spain, and the Netherlands, all of whom remained at war with the British as long as the Americans did. During the first years of the Revolution, most of the American military stores were supplied by France and Spain, partly as the result of the efforts of the pro-American playwright Beaumarchais. In addition, Catherine the Great of Russia promoted the League of Armed Neutrality, a militantly anti-British coalition of states seeking to rescue the freedom of the seas from the insolent and overbearing Royal Navy. The armed neutrality comprehended Russia, Denmark and Norway, Sweden, the Holy Roman Empire, Prussia, Portugal, and the kingdom of the two Sicilies.

History books today allege that the European Friends of America were simply geopolitical cutthroats, opportunist aggressors who took advantage of the American revolt in order to gang up on their resented British rivals. This ignores the fact that there was a community of principle against the British involved.

What gave Franklin his great resonance among the French and the other Europeans was his intersection with a later generation of the Leibniz networks among scientists, government officials, and men of letters. These circles sensed in Franklin an heir of the great Leibniz.

And what about the Venetian oligarchs, the great defenders of Republican liberty? They refused to accredit American ambassadors and they hired out a third of their navy as an auxiliary to the British fleet. During the American Revolution, the Venetians were the Hessians of the seas. As for Catherine the Great, the British have never forgiven her. They're still spreading stories about her to this day.

Hear ye! Hear ye! It's Anno Domini 1750 and all is not well. His Majesty's Parliament prohibits us from all further iron making. No new furnaces or forges. He bans our manufacturing of finished goods. His high mightiness thinks he can condemn us, and our posterity, to perpetual serpdom. Look to your future, Americans! Hear ye! Hear ye!

America's colonists had good reason to be alarmed in 1750, and they already had revolution on their minds. Benjamin Franklin had reached the ripe old age of 44, though George Washington was only 18. Another quarter century would pass before Massachusetts militiamen fired on British troops at Concord Bridge in 1775. But Britain's Iron Act, of 1750 constituted a decisive act of war against any further American efforts to live as human beings created in Imago Dei. Without scientific discovery and technological progress and a people seeking to delight in them, there would never have been an American Revolution. Without a growing iron industry, new tools, machines, engines, or even implements of war could simply not be produced. During the first half of the 18th century, against what often appeared to be impossible odds, the American colonies had sustained and even widened a political war against British oligarchical rule.

Their leaders were guided by the ideas of Leibniz, aided by the bold work of Jonathan Swift, and were committed to founding a sovereign American republic. Contrary to mythologies prevailing then and now, the English-speaking colonies of North America were never ruled by a benevolent Mother England. John Quincy Adams' famous reference to Our Lady Macbeth Mother was a diplomatic way of summarizing the blunter descriptions used by generations of Americans. The rotten core of British colonial policy was to resort to pillaging and slaughtering America's frontier settlements in order to prevent any westward development. Britain preferred to confine its colonial subjects largely to manual labor, producing raw materials for delivery to British ships along the Atlantic seaboard.

The slaughtering was generally left to Indian tribes, whether based in the American colonies or in Canada, which remained in French hands until 1763. During the 18th century, such murderous assaults on New England were jointly run by British and French oligarchical circles. The two monarchies had even signed a treaty in 1701 prior to declaring war on each other in 1702, whereby the British guaranteed safe passage for tribes from French Quebec to attack New England throughout the war without any interference from the pro-American tribes of the Iroquois Five Nations. Under this Hobbesian arrangement, whole towns in Massachusetts were reduced to ashes from 1704 to 1708, their men massacred along with their women and children, except for those dragged off to captivity in Quebec.

Massachusetts Royal Governor Thomas Dudley made a killing selling arms and supplies to Canada for use against the very colonists he supposedly governed. And the British Navy left the New England coast utterly unprotected, enabling French ships to destroy 140 ocean-going vessels of Massachusetts alone by 1705. For generations, many of the French-run tribes viciously exploited and goaded to acts of barbarism were run by Jesuit priests of the time, who also instructed the Indians in such pieties as the claim that American colonists worshipped the Antichrist. These Jesuits, who pretended that their evil oligarchical service was somehow Christian, were so notorious that they were publicly condemned not only by leading American colonists such as Cotton Mather and Benjamin Franklin, but by whole colonial legislatures as early as 1700 in the case of New York. Urgent colonial appeals to the mother country for assistance or military countermeasures were repeatedly ignored, others were granted nothing more than fraudulent pledges of support.

The one British military expedition against French Quebec ordered by Queen Anne to strike up the St. Lawrence River in 1711 to root out the Indian threat came and went without firing a shot. It was sabotaged through the Venetian party's political and military chain of command.

The foul arrangement to prevent any further development by the American colonies would remain in place. America's problem was that any hope of independence from Mother Britain depended on attaining a level of internal economic development sufficient to sustain a military capability of its own. The colonists, after all, could not ward off Indian massacres simply by wringing their settlements with political pamphlets. Nor did Britain permit the colonial militias to arm themselves. beyond some rusty flintlocks and old blunderbusses, except as Britain saw fit when it was at war with France. Even that limited opportunity disappeared from 1713 until 1742, when war between the two powers resumed.

Especially since Robert Walpole's rise as Prime Minister in 1721, Britain under King George I and George II had become the very model of the modern satanic state, operating according to the doctrine of Bernard Mandeville and the Hellfire Clubs, and Walpole's own maxim that every man has his price. Britain soon lay in its own ruins. Bankrupt, depopulated, and deranged, the British declared war on Spain in 1739 over Spanish refusal to renew Britain's monopoly on the slave trade in the Americas.

France, meanwhile, had tightened its military encirclement of the British colonies in America, pressing in from the Gulf of Mexico, the Mississippi River, and the Great Lakes. Then in 1740, the French completed a vast new fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, which guarded the entrance to the St. Lawrence River and threatened the coast of New England. The British, desperate for any loot they could get their hands on, launched an undeclared war against France in 1742. Early in 1744, orders from London reached the American colonies, directing them to prepare for offensive war. A long awaited opportunity had arrived. Americans prepared for war all right, but they launched a war for nation building on a level that Britain could not match. They launched a war of ideas.

In April 1744, Benjamin Franklin unveiled in Philadelphia his newly founded American Philosophical Society, recreating the institution first founded by Increase Mather in America in the 1680s on the model of a Leibnizian Academy. Intended to function as a scientific committee of correspondence, it was Franklin's attempt to begin unifying the American colonies around a cultural commitment to reason, an indispensable requirement for a strong republic.

He had begun the project the year before with the publication of his proposal for promoting useful knowledge among the British plantations in America, urging that one society be formed of virtuosi or ingenious men residing in the several colonies, to be called the American Philosophical Society, who are to maintain a constant correspondence.

The proposed subjects of correspondence included botany, medicine, geology, metallurgy, new mechanical inventions for saving labor, and such applications as milling, transportation, and irrigation. All new arts, trades, and manufactures that may be proposed or thought of surveys, maps, and charts of particular parts of the sea coasts or inland countries, course and junction of rivers and great roads, situation of lakes and mountains, nature of the soil and productions, new methods of improving the breed of useful animals, introducing other sorts from foreign countries, new improvements in planting, gardening, and clearing land, and all philosophical experiments that let light into the nature of things, tend to increase the power of man over matter, and multiply the conveniences or pleasures of life. Franklin's proposal for the American Philosophical Society was a task force agenda for organizing a nation state.

The founding group in Philadelphia was drawn from Franklin's own original organizing committee, the Junto and its improvement clubs, He made a special trip to New York in 1744 to recruit James Alexander, a protege of Jonathan Swift's old friend Robert Hunter, governor of New York from 1710 to 1719. Swift, the brilliant polemicist and political strategist who was Leibniz's leading English-speaking ally, had arranged both Hunter's appointment as governor by Queen Anne and his induction into the Royal Society. Now, this is fun. James Alexander, heir to the Scottish earldom of Stirling, took part in the Scottish rebellion of 1715 against Britain's newly installed Hanoverian King George I, the enemy of Leibniz and the very stuff which the Venetian party dreams were made of.

Robert Hunter, himself a Scot, had known Alexander's family, and somehow, young James was spared the typical fate of being drawn and quartered and was deported to New York instead. There he became one of Hunter's most trusted friends, was trained in mathematics and surveying, learned astronomy directly from Hunter, and earned appointments from him to several offices in New York and New Jersey. As a member of the American Philosophical Society, James Alexander was the astronomer in charge of American preparations in 1753 to record the transit of Mercury. He also organized support for Franklin's first attempt to politically unify the colonies, the 1754 Albany Plan of Union.

His son, William Alexander, became one of George Washington's most trusted generals during the American Revolution. To bug the British during the war, he flaunted his Scottish title as Lord Sterling and helped expose the treasonous plot by the Conway Cabal in 1778 to remove Washington from command of the Continental Army. James Alexander had many blessings to count, and clearly it helps to defy the axioms of imperial opinion, especially if you wish to become a scientist and a philosopher and build a republic. The pursuit of knowledge was not going so well on the British side.

The English artist William Hogarth, another friend of Jonathan Swift, commented on the problem in a 1738 engraving of a leading Oxford professor, lecturing his students on the properties of a vacuum.

Franklin's nation-building agenda in 1744 was not intended merely for abstract contemplation. Indeed, given Britain's authorization to mobilize for offensive war, his proposals fueled a series of bold measures to smash the longstanding wall of containment which British and French oligarchical interests had maintained. Walpole was already a dead duck, and the collapse of his government had also left significant cracks in Britain's colonial machinery. A new governor had taken office in 1741 in long-suffering Massachusetts, William Shirley, who was already familiar with the colony and with the circles of Benjamin Franklin. The French military governor commanding the new superfortress at Louisbourg launched attacks on Nova Scotia.

In 1744 Shirley's warnings to London that New England's fisheries were in danger went unheeded. He began formulating a plan to accomplish the impossible. He proposed to the legislature in Boston during a secret session in January 1745 that the colony immediately prepare an expedition to take Louisville, the greatest French fortress in the New World, on its own authority and without the involvement of Britain. After recovering from shock, the legislators approved the plan, authorized bills of credit to pay for it, and mobilized more than 3,000 Massachusetts militiamen, a squadron of ships totaling over 200 guns, all the artillery they could get their hands on, and 90 ocean-going transports.

After the fleet sailed from Nantasket Rhodes on March 24th, 1745, Shirley sent a letter to London, which he knew would take two months to get there, informing His Majesty's government that New England forces would besiege Louisbourg with 4,000 men. The plan was so bold even down to attacking the fortress from behind at a point which the French thought impossible, that it worked.

News reached Boston at 1 a.m. on July 3rd, 1745, that the fortress had surrendered after a lengthy and devastating siege. Bells pealed, cannon roared, cheering throngs filled the streets, jubilant celebrations with bonfires and fireworks were held throughout the colonies as the word spread. With no assistance of any kind from Britain, untried, poorly equipped New England militia had taken out a French fortress boasting enormous firepower, and so vast that it contained an entire city within its walls. It was a stunning victory, especially in the minds of Britain's ruling circles, who regarded it, one might say, as a horrifying triumph. Americans eagerly anticipated the imminent removal of the French Jesuit Indian threat to the colonies and a British military follow-up on their spectacular achievement in the opening round. But British and French oligarchical circles were already at work redrawing future settlements to preserve their joint containment.

The British decided merely to project the illusion of supporting the colonies' hopes until the opportunity to take Canada had passed. Meanwhile, Louisburg was to be held at American expense, with nothing more from Britain than the promise that the garrison would be relieved by troops from Gibraltar someday.

More than 3,000 New England militiamen remained encamped at Louisburg in the summer of 1745. Their siege had reduced most of the quarters within the fortress to ruins, and relief was urgently needed. The drinking wells were dangerously contaminated and the island was completely dependent on external supplies. A major military and civil reconstruction effort was required, but two months passed with no sign of activity from London. Rumors spread in Boston that Britain was planning to return Louisbourg to the French. His Majesty's government threw a bone to Governor Shirley appointing him a colonel in the British Army to command regiments to be raised in America. Officers' commissions had been claimed for the British, however, and surely reported, men will not enlist here except under American officers. The British, meanwhile, left the New England regiments at Louisburg to twist in the wind. All through the fall and further isolated during the long winter, suffering from fevers, dysentery, and lack of supplies. They waited in vain for the relief promised from Britain.

By the time a modest detachment of troops arrived from Gibraltar in April 1746, ten months after the French surrender, nearly 900 New England militiamen had died. The survivors finally sailed for home, most of them from Massachusetts, bringing with them a deepening hatred of British rule. America's future was beginning to take shape in Boston in more ways than one. And inevitably, it reflected something of the past.

The leading scientist in America at the time was Harvard Professor John Winthrop. the direct descendant and namesake of both the Republican founder in 1630 of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and his son, who extended that constitutional liberty during the 1660s as governor of Connecticut. The Connecticut Winthrop was a scientist in his own right, and had corresponded with the young Leibniz.

Professor John Winthrop held the only academic chair in science in America. Like his fellow Bostonian, Benjamin Franklin, he was a protege of Cotton Mather and, like Ben, was something of a child prodigy. He was admitted to Harvard College at the age of 13 in 1728, the same year Mather died. He graduated in 1732, the year George Washington was born, and was appointed professor of mathematics and natural and experimental philosophy in 1738.

We know from student lecture notes that he included Leibniz in his course of study and that he had great fun using physical models to Socratically demolish the empiricist nonsense of Descartes. Benjamin Franklin had visited Boston in 1745 and returned again in 1746. He reports in his autobiography that it was then at Boston that he “witnessed experiments in electricity, a subject quite new to me”. On May 10th, 1746, John Winthrop presented at Harvard the first controlled experiments in America in electrical phenomena. He remained one of Franklin's most trusted friends throughout his life, which was ended by pneumonia in 1779. He was also at the very center of America's Republican networks.

He was consulted by George Washington during the French and Indian War, and again during the Revolution when Washington appointed him to oversee the production of munitions for the Continental Army's siege of British-occupied Boston. John Winthrop's students included John Adams, Sam Adams, and John Hancock, who were in constant communication with him during the Revolution.

When John Adams agonized over whether the Continental Congress should declare independence from Britain, Winthrop warned him in April 1776 that unless the decision were made pretty soon, Massachusetts would do it for themselves. In 1746, after the capture of Louisburg, the British had learned what Massachusetts could do on its own and already feared the threat of American independence.

His Majesty's government, as Franklin later charged, affected to entertain a project for the reduction of Canada, merely by way of a feint to secure peace. The British went so far as to load up an expeditionary force on transports at Portsmouth, England, providing grounds for military countermeasures against America by France. Lord John Russell, a cabinet member from one of Britain's most infamous ruling families, then objected that a British expedition might further a tendency toward independence by the colonies. The troops were unloaded, and the expedition was canceled.

Jesuit-run tribes, meanwhile, had overrun settlements from Rochester, New Hampshire, to Saratoga, New York, and in 1746 seized Fort Massachusetts, the key to that colony's western defense. Within lands claimed by Virginia beyond the Ohio River, the French were building up Forts Miami, Louis Atenon, and Vincennes. In the summer of 1747, a French raiding party even ventured up the Delaware River to within 20 miles of Philadelphia.

In that same year, the British Ministry declared that the American regiments must be disbanded, as it put it, as cheap as possible, and that no more military actions be undertaken by the colonies. In 1748, at the Treaty of Aix-La-Chapelle, ending the war in Europe, the British gave Louisbourg back to the French in exchange for the port of Madras, India, and future looting by the British East India Company.

A Swedish traveler in America at the time who visited with Benjamin Franklin reported from New York, the English government has therefore reason to regard the French in North America as the chief power that urges their colonies to submission.

If one steps back to comprehend what most Americans understood from these events during the 1740s, then one comprehends why the American Revolution was indispensable. Without it and without the power of the United States as a constitutional republic, Western European civilization, as created by the Renaissance, would not have survived. And had colonial Americans not fought for that higher conception of man against the bestial notions of the British oligarchy, we could never have won the War of Independence.

Yet the British and their American apologists, even to this day, twaddle on about their ‘special relationship and the common bonds of the Anglo-Saxon race’. The American Revolution was simply the result of a bit of misunderstanding, you see, and perhaps one or two tactical or administrative blunders.

Tom: The special relationship, Reggie, that ought to be right up your alley.

Reggie: It is the very core of my existence. Blood is thicker than water. Tom, you Yanks have to choose between your Anglo-Saxon kin across the sea and those bloody wogs.

Tom: What is a wog, anyway, Reggie?

Reggie: Very simple. Wogs begin at Calais. I say that every time I address the House of Lords. The Anglo-American relationship is fundamental.

Tom: Sounds right to me.

Reggie: Very staunch, Tom. Think of old Sir Winston. What a leader. He was always ready to fight to the very last American!

The reality was that British policy was consistent and consistently rotten. In terms of policy essentials, what they did in the 1740s during the War of Austrian Succession was the same thing they did during the French and Indian War and attempted to do again during the American Revolution and throughout our history as a nation.

Simply put, their policy has always been we will not permit the existence of an American republic. But Americans weren't stupid. At least they weren't in the 18th century, when they also happened to have the most literate population anywhere in the world. And they had an agenda for nation building, as Franklin had summarized it in 1744, for the American Philosophical Society. The work was already underway. The new territory. which America wished to develop was not Canada, but Virginia's vast colonial claim to the West, which then included what became the states of West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and the portion of Minnesota east of the Mississippi River.

In Virginia, in 1747, Lawrence Washington, George’s older half-brother, founded the Ohio Company, with the backing of Lord Fairfax, the proprietor of Virginia's northern neck, a royal grant extending across most of northern Virginia all the way to the head spring of the Potomac River in the west, deep in the Allegheny Mountains. Proposed as a private venture to circumvent direct royal government, the company proposed to settle half a million acres just beyond the Fairfax grant, southeast of the headwaters of the Ohio River at what is now Pittsburgh.

The Crown granted the Ohio Company petition in 1748, and in March 16-year-old George Washington set off with a small party to begin surveying the Appalachian reaches of the Fairfax Grant towards the Ohio country. By the fall, The Ohio Company had begun recruiting German immigrants, especially iron workers, to overcome the shortage of skilled labor resulting from British repression of colonial iron making. Soon, a string of bloomeries and forges for iron making were underway in the Shenandoah Valley. At Lancaster, Pennsylvania, skilled German metal workers began producing the first rifles in America, spiral grooved and deadly accurate at more than 250 yards. The ohio company was now the spearhead of a growing effort to break through to develop the west, and in 1750 the British responded in their typical fashion by issuing the infamous ‘Iron Act’, decreeing a zero growth policy for America.

Franklin drafted and privately circulated his reply in 1751, published four years later as his “Observations concerning the increase of mankind”. He declared that “those who devote themselves to the promoting of trade, increasing employment, improving land, et cetera, and the man that invents new trades, arts, or manufactures, or new improvements in husbandry, may be properly called fathers of their nation, as they are the cause of the generation of multitudes”. Therefore, he said, “Britain should not too much restrain manufacturers in her colonies. A wise and good mother will not do it.” So much for Britain's maternal qualities.

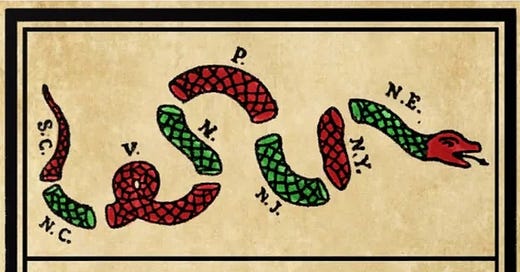

In 1754, commanding the Virginia militia, George Washington forced the issue of developing the West when he fired on French troops who had pushed into the interior of southwestern Pennsylvania at Jumaville Glen. Franklin accelerated his drive to politically unify the colonies and issued his famous cartoon summarizing the crisis for America with the motto JOIN, or DIE.

Widely reprinted at the time, it later became a symbol for the American Revolution. In the ensuing French and Indian War, Britain decided it finally had to make a show of force in support of its American colonies. The British Army's only significant campaign on the Western frontier was designed to fail. And despite George Washington's best efforts, ended in Braddock's defeat in 1755, well before reaching Fort Duquesne. The British chose instead to attack French Canada, and with the cost of many American lives, a supposed victory was obtained.

This time, His Majesty's government wanted to return all of Canada to the French in return for the tiny island of Guadeloupe, which Britain fancied as a great convenience to its Caribbean slave trade. The furor in America, loudly conveyed in London by Franklin himself, forced the British to settle for taking Canada. The Jesuits, however, were left in place, even though they were being kicked out of both France and even the Habsburg Empire at the time.

Within weeks after word of the Treaty of Paris reached America in 1763, the worst Indian War America had ever seen broke out, drawing tribes from as far away as the northern Great Plains and western Canada, leveling nearly every outpost west of the Alleghenies, and driving deep into the colonies along the Atlantic coast.

It was a coordinated onslaught on a vast scale. And this time, every single assault came through territory administered by Great Britain. With professions of his infinite care for his poor subjects in America, King George III set forth in the wake of the slaughter his Proclamation Line, prohibiting Americans from crossing the eastern mountain chain ‘for their own safety’.

Not to put too fine a point on it, we told George to ‘stuff it’ and continued to explore the West and plan the roads and canals and new technologies which would be required to build a nation. I can tell you now, since it's not a secret, that we won the American Revolution. It's a fascinating story, much of which is scarcely known, and just the sort of thing you might imagine I could go on for hours about, but another time perhaps. But I will ask you to look ahead for a moment to something which occurred in 1785 when Benjamin Franklin returned following his long years in France, having negotiated a much better treaty of Paris in 1783 on behalf of the independent United States of America.

Franklin had examined some of the work on hydrodynamics by the Swiss scientist Daniel Bernoulli and was intrigued by the possibilities of water jet propulsion using a steam engine. Both, Bernoulli's uncle and his father, were scientific allies and contemporaries of Leibniz. Jacques Bernoulli was well known for his applications of Leibniz's calculus to problems in geometry. And Daniel's father, Jean, had played a leading role on Leibniz's behalf in the controversy with Isaac Newton.

In Philadelphia, on December 2nd, 1785, Franklin presented a paper to the American Philosophical Society entitled “Aides to Navigation”, which included some discussion of Bernoulli's theories on water jet propulsion. In Virginia, George Washington was already discussing the possibilities for developing a steamboat using water jet propulsion. With James Rumsey, his chief engineer for the Potomac Canal Company, Washington met with Rumsey at Berkeley Springs, Virginia, in September 1784. While staying at Rumsey's Inn named the ‘Sign of the Liberty Pole and Flag’, Rumsey showed him a model of a mechanical boat he was working on, and Washington was so enthusiastic he promptly wrote him a certificate of recommendation. Washington reported that he had examined the powers upon which it acts and declared that it was his “opinion that the discovery is of vast importance and may be of the greatest usefulness in our inland navigation.” On December 3rd, 1787, on the Potomac River at Shepherdstown, now West Virginia, James Rumsey gave a special demonstration of his water jet propelled steamboat. The turnout of cheering citizens included a large contingent of veterans and former officers of the Continental Army. This was what they had fought for.

Webster Tarpley:

Everyday life in the modern world is for most people a self-evident array of expectations. We expect hot and cold running water, indoor plumbing, central heating, electric lights, air conditioning, and the usual array of labor-saving appliances, which today might include a computer, a printer, or a fax. We expect to have music in the home whenever we want it.

When we travel, we expect a modern automobile, train, or a jet aircraft. When we are sick, it is clear that we want to have access to a qualified doctor, and if need be, to a fully equipped hospital. We want medicine, x-rays, CAT scans, MRIs, and so forth.

The problem is that for the oligarchical mind, it is very far from self-evident that the vast majority of people ought to have access to these amenities. The oligarchical party has seen the introduction of each of these modern conveniences as a violently partisan issue, precisely because they are a component of progress and an enhancement of human productivity.

Most people of today do not remember how dark, cold, and sick most of human life on this planet has been. Today, it is mainly natural disasters that remind us. Human history has been full of valuable human beings living in poverty, suffering in drudgery, and dying young? How many lives have been needlessly forfeit to pneumonia, gangrene, a burst appendix, influenza, polio, or the complications of childbirth?

Most of the planet still lives this way today. All of the cultural presuppositions of modern life had to be fought for tooth and nail against an oligarchy that instinctively saw its own interests as tied to misery, degradation, and suffering for the many.

Anton Chaitkin:

The ancient Greek dramatist Aeschylus told the truth in his play on the legend of Prometheus that Prometheus gave us all the advances of human knowledge, fire, science, and power over nature, that he took man's side against the pagan rulers of the earth, the Olympian gods, who planned to exterminate mankind. Zeus imprisoned and tortured him, but Prometheus would not submit. He foresaw that Zeus was sowing the seeds of his own destruction and overthrow.

Gottfried Leibniz proposed that the modern nation must sponsor science, research, education, and new manufacturing to defeat tyranny and backwardness. Leibniz and his followers actually accomplished this. The American Revolution, the science breakthroughs, the important inventions, the great industries, were all deliberate projects of a single Promethean leadership faction.

All the progress we have had has come from forethought or planning for it by these Prometheans. Prometheus means forethought.

The Anglo establishment who fought against these developments boldly lied that they themselves gave machine power to the world and high living standards. These liars are the same merchant aristocrats that ran the holocausts of slavery and opium. But their history books claim that modern conditions came only from “the free market”. That industry appeared because private financial gain was totally unrestrained.

Communist writers agreed with this ridiculous version of capitalist history. So the poor anti-communist citizens of Eastern Europe or the Third World are left historically in the dark and at the mercy of the British sharks who try to stop their progress, just as they have always tried to stop Western progress.

When Benjamin Franklin arrived in England in 1757 as the colonists' political representative, Britain's rulers considered him ‘the most dangerous man in the world’. He had founded modern electrical science. He was the anti-imperial intelligence chief with a worldwide network of allies to back our fight for national development.

Now, England was then a filthy, backward country with no roads between cities, No canals, no railroads, no power machines, no factories, no plumbing, no running water. The people lived in poverty, cold, and darkness, and died young.

Franklin moved into a house in London, the empire's capital city. To counter the British ban against American industry, Franklin and a small circle of his followers began industrialization right there in Britain to make it impossible to contain. Franklin established Birmingham as the headquarters of his quiet revolutionary English faction. Matthew Bolton, a buckle maker, was his right-hand man. The Franklin Circle took over managing the estate of the Duke of Bridgewater, west of the little town of Manchester. Recruiting the idealistic young Duke to their scheme, they built England's first canal. This Bridgewater Canal got land buying privileges from Parliament, where the Duke and some friends were in the House of Lords.

The Franklin Bolton Group cut the canal from the Duke's coal-rich little mountain across the 10 miles to Manchester, completing it in 1761. In an instant, Manchester had abundant cheap coal from the Duke's coal mine, the coal price being fixed by the law that set up the canal.

Tens of thousands of families moved to the town for high paying new jobs and coal heated homes. Manchester immediately became England's first industrial city. Franklin's Birmingham Circle now built canals to Liverpool, Hull, Bristol, and London. Coal replaced local trees as England's fuel. Goods could now be shipped cheaply, and real industry was suddenly possible.

Franklin now started on the next step, the development of a practical steam engine. Franklin introduced to his English group Dr. William Small of Virginia, formerly Thomas Jefferson's mathematics teacher and musical partner. Dr. Small became industrial manager at Bolton's new SoHo plant. Small hired a young canal surveyor, James Watt, as principal researcher.

Bolton, Small, and Watt carried on the steam power project under Benjamin Franklin's personal scientific leadership. Using for their experiments, steam machinery developed long before by Denis Papin and Gottfried Leibniz. Franklin then met the young clergyman Joseph Priestley and convinced him that scientific work could help mankind more than disputes with the Church of England.

Priestley took Franklin's assignment to write a history of electrical knowledge to begin his career. Priestley discovered the breathable element in air, discovered how plants consume and renew what animals exhale, and how light grows green plants. Franklin's agent in France, Antoine Lavoisier, called Priestley's element oxygen.

Lavoisier created combustion science, and he and Priestley laid the basis for modern chemistry. Priestley's brother-in-law, Iron Master John Wilkinson, bored out a perfect steam cylinder that made the Franklin group's steam engine work. Wilkinson then used the engines to power up his mills, England's first modern steel mills.

Clergyman Edmund Cartwright, a member of the Franklin Circle, invented the first cloth-making machines using the group's steam engine. Franklin brought in the young Pennsylvanian, Robert Fulton, to apprentice with Bridgewater, Bolton, Watt, and Cartwright. Fulton would later make the world's first commercial steamboat in America. These latter developments by Franklin's group Inside England occurred under increasing police surveillance right through America's Revolutionary War against Britain.

Franklin's Birmingham Circle was soon hit with staged riots and police crackdowns and was broken up. The profitable new industries came under the management of swindlers who cut wages and worked women and children to death. British economics writers claimed the swindlers created the industries. Britain maintained strict tariff protection while demanding that other governments must not sponsor industrialization.

In 1787, the United States Constitution was designed by Franklin, his fellow Nationalists, George Washington, and allies, including their protege, Alexander Hamilton. As the first Treasury Secretary, Hamilton modeled the new government's program on the thought of Franklin and on Colbert, the patron of Leibniz. Hamilton's National Bank would provide easy credit for productive investment. High tariffs would promote new industry. And the government would build great transportation projects.

Reggie: I wish this fellow would nap off Those so-called founding fathers were not working for the public interest. They were working to line their own pockets. Hamilton was working for the rich and the well-born. He said so himself.

Tom: That guy Hamilton sounds like big government to me. And the era of big government is finally over.

Franklin and Hamilton, the founders of America's anti-slavery movement, put forward this industry building program as the only practical plan to end the plantation slavery system.

They rejected Adam Smith's doctrine that Americans were destined to be only planters, slaves, and peasants. But British-allied Boston merchants and southern slave owners blocked the founders' tariffs and canal plans, and American industrialization was delayed. The anti-big government faction virtually dissolved the army and navy. So the British stepped up attacks on US shipping and frontier settlements.

The nationalists rallied the country to defend itself in the War of 1812 against Britain. These nationalists then revived the Franklin-Hamilton program. Beginning in the mid-1820s, it was mainly four men who directed America's dramatic shift to industrial power and urban civilization. These leaders were

Matthew Carey, Franklin's Irish Catholic revolutionary agent, a political prisoner of the British, who became a Philadelphia publisher and economist. Carey and his friends recreated Franklin's old nationalist movement with its headquarters in Philadelphia.

Nicholas Biddle, president of the Bank of the United States, which was also in Philadelphia.

John Quincy Adams, US President and later the anti-slavery leader in Congress.

And Henry Clay, Speaker of the House and later Senator.

President John Quincy Adams in 1825 assigned the Army Corps of Engineers to plan the first railroads. Army engineers surveyed and designed 61 railroads before ‘the free trade crazies’ made it illegal in 1837. American railroad construction was financed by government, state, county, local, and later federal government with cash grants, loans, government bonds, stock purchases, land grants, and every conceivable form of subsidy.

Government backing created America's iron industry. We had only local, small-scale iron production until Matthew Carey's educational campaign moved the nation to pass high-tariff laws. As a direct result of tariff protection, American iron output more than tripled in 10 years to 1832. Then it stagnated for 10 years under free trade. Then more than tripled again in five years under Henry Clay's last high tariff.

Pennsylvanians, Biddle and Carey, got their state legislature and neighboring states to build 1,000 miles of canals. These waterways started bringing hot burning anthracite coal to market. Under the Biddle-Carey scheme, anthracite coal production rose from 400 tons in 1820 to 8 million tons in 1855. This anthracite was the first coal to be used for American industry.

Clay in the Senate, Adams in the House, and state leaders like the young Abraham Lincoln in Illinois worked with Biddle's Bank of the United States to finance new canals and railroads westward from Pennsylvania. This created the Midwest farming communities and industries, and a Illinois nationalist political base. But by the 1830s, Britain's merchant partners, called the Boston Brahmins, and the British-run secessionists in South Carolina were dragging down America's modernization. They closed the US bank, blocked national infrastructure, stopped protective tariffs, and stifled industry in the South.

The nationalists now reached out for allies, as Franklin had done. They planned to build industry and political strength in nations overseas who could stand with them against the British Empire. Their link to European science in the Leibniz tradition would magnify the economic and military power on the side of freedom.

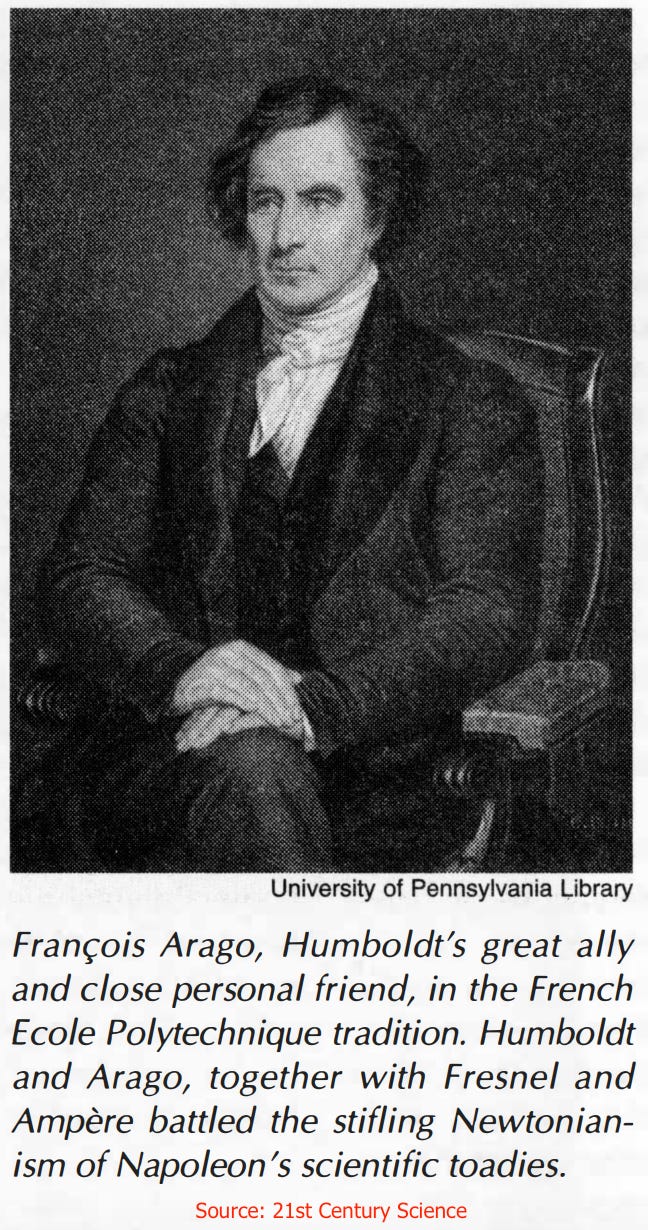

The Ecole Polytechnique in Paris was the world center of research and the training of scientists. The British conquered and smashed France in 1815. German scientist Alexander von Humboldt arranged with American officers for teachers and material from the Ecole to be brought over and set up at the US Military Academy at West Point.

The Ecole geometric methods were used to train America's first really qualified engineers. And those West Point Army engineers were the ones designing America's first railroads. Now this is how electricity developed in that period. First in 1820, the Danish researcher Ørsted, who had studied at the École Polytechnique, showed that a current from a battery through a wire would pull a nearby magnetic needle away from pointing north. Ørsted wrote that it was odd that Franklin's discovery of lightning's electrical nature has not aroused an inspired representation from any great poet. The discovery was the fruit of scientific thinking, but was introduced into the world through an heroic act.

The Frenchman Arago, who taught geometry at the École, discovered that a current passing through a wire could make a neighboring piece of soft iron magnetic. The French scientist Ampere, who taught mathematics at the Ecole, discovered that two neighboring wires would either attract or repel each other depending on the direction of the currents in them. Ampere concluded, that natural magnetism is electricity within the material. And he formulated the mathematics of electromagnetism. In 1825, an Englishman named Sturgeon wound wire a few times around a piece of iron and could pick up nine pounds with it while a current was passing through.

Between 1829 and 1833, the American school teacher Joseph Henry made big breakthroughs. In accord with Ampere's theory, Henry made very powerful electromagnets with multiple windings of wire till he could lift 3,000 pounds. By turning his artificial magnet rapidly on and off, he first made a magnet induce a strong electric current in a wire.

Joseph Henry made the first little device, moved by electromagnetism, the first electric motor. He first sent powerful currents over long distances. He first magnetized iron at a distance. And by ringing a bell at a distance in a code pattern, he made the first experimental telegraph.

Then over in the German state of Hanover at Göttingen University, the mathematician Carl Gauss and his research partner, physicist Wilhelm Weber, excitedly picked up the leads of the American Joseph Henry. Gauss was the world's greatest scientist, a defender of Leibniz, and closely tied to the American nationalists. He was an advisor to the US Coastal Survey, and his three sons had emigrated to America.

Hear ye, hear ye. German astronomer Gauss sends a message by electric wire two miles in less than a minute. He says, telegraphs to be installed on all German railroads. The new invention could unify all of Russia. The British say it can't work. Here are ye! Here are ye!

Gauss and Weber built the world's first long-distance electric telegraph in 1833. Gauss intended it as a strategic tool the Americans and their allies could use with railroads to make unified nations that could overcome British power. And the Americans were moving to do just that. Their main international organizer was the German economist Friedrich List, who had been imprisoned for his anti-British nationalism and went as an exile to Philadelphia. List helped Biddle and Carey educate the country on nationalist economics as they launched modern America. The nationalists arranged for the honored former political prisoner, List, to go back to Europe as a diplomat representing the United States, stationed in France and Germany.

Liszt's writings inspired all of Europe to emulate the nation-building principles of the American Revolution. On Liszt's initiative, 18 little German states united. giving birth to Germany as a single nation, with tariffs protecting new German industry from British trade war. Friedrich List organized Germany's first railroad. First railroads. The American strategic program was for France, Germany, and Russia to cooperate in rapid modernization stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to China. To be sure, the alarm bells were going off in the British Empire strategy offices. Early in 1837, two American scientists sailed together to Europe on an intelligence and political mission that would deeply affect world history.

These two travelers were electrical researcher Joseph Henry and the young physicist Alexander Dallas Bache. Bache was a Philadelphia nationalist leader who had publicized Joseph Henry's work, thus allowing Gauss and Weber to act on Henry's breakthroughs. Taking separate paths around Britain and the continent, Henry and Bache were to contact Europe's leading thinkers to prepare a sharp upgrading of American scientific and military power.

Nicholas Biddle and his colleagues had commissioned Baesch for the trip because of Bache's unique qualifications. He was the great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin. This alone would get him a big reception in Germany's Göttingen University. where his celebrated ancestor Franklin had gone 70 years earlier to campaign for America's cause. Bache was also a brilliant West Point Army engineering graduate and leader of the Nationalists Research and Development Complex at the Franklin Institute and the University of Pennsylvania. In December 1837, Bache arrived in Berlin and took up temporary residence with Alexander von Humboldt, America's greatest strategic advisor.

Bache was preparing with Humboldt his imminent visit with Gauss and Weber at Göttingen University in Hanover. But one week after Beche's arrival in Berlin, before he got to Göttingen, The British royal family expelled Wilhelm Weber and six other professors from the university and surrounded Gerdingen with troops to prevent political demonstrations.

The British royal family at that time still ruled both England and the German state of Hanover, the original home of the British royal family. A month before Beche arrived in Germany, Hanover's king, Ernst August, a son of King George III, had revoked Hanover's constitution and liberties.

When Weber and other famous teachers protested, the British king expelled them and moved troops. Despite the British imposed terror, Baesch arrived at Göttingen the next month and met with Gauss and Weber. The Gauss-Weber research team was broken up, but the adversity and oppression forged strong bonds of friendship between Baesch and the greatest European scientists.

This relationship would shape American science in its most important advances. These scientists understood the British problem. When Carl Gauss received the Copley Medal from the British Royal Society, he told his children that he would have sold it for its metallic value and given them the money, but it was worth too little. Following his 1838 return to America,

Alexander Dallas Beche recruited a handful of loyal and patriotic science associates into a small junto. In private, they called themselves the Florentine Academy, or jokingly, the Lazzaroni, an Italian term for a bunch of filthy beggars. Working with Gauss and Humboldt, Bache and his group created a military industrial science complex to secure the defense of the American Republic.

This is what they accomplished in the next seven or eight years. Baesch organized Philadelphia's public schools along the lines of Prussia's excellent free compulsory school system. He built up Philadelphia's Central High into the first great public secondary school in America, the model for all other high schools. The Russian czar hired former U.S. Army engineer George Washington Whistler to build Russia's first railroad from Moscow to St. Petersburg. The locomotives were shipped to Russia from the Baldwin Company, part of the Philadelphia Nationalists Research and Industry Organization.

Bache studied with Gauss the Earth's magnetic field. For this purpose, Bache hired and trained an assistant named William Chauvenet, who began teaching science to sailors at a Philadelphia Naval hospital. These classes were transferred to a Fort at Annapolis, Maryland, and Bache arranged for this to become the United States Naval Academy. Bache himself was appointed head of the US Coast Survey. Bache made it the main government agency for employing and training scientists.

Union naval victories in our Civil War were ensured largely because Bache's teams had mapped the current and coasts, while Bache's teachers had brought Gauss's mathematical science to our naval officers.

In 1843, Henry Clay led the US Congress to pay for American implementation of the telegraph. It was Samuel Morse's version of the earlier invention of Henry, Gauss, and Weber. Congress accepted Bache's recommendation for Joseph Henry to be the first chief of the new Smithsonian Institution. Henry created the modern weather service based on reception of reports by telegraph. Meanwhile, Members of Bache's Lazzaroni set up real science programs at both Harvard and Yale and took those colleges temporarily out of the hands of the Anglophiles. A Bache ally at Yale, chemist Benjamin Silliman Jr., reported in 1855 that petroleum under the Pennsylvania ground could be cracked and refined into valuable fuel. This started America's oil industry. Bache was the recognized chief of America's scientists.

At the outset of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln asked Bache and his colleagues to sort out the loyalties of the entire Naval Officer Corps at a time when many military officers were deserting to the slave owners' rebellion. While the British built cruisers for the Southern Navy to sink US ships, Bache and his fellow strategists decided to build ironclad monitor warships that could defeat both the Southern and the British Navy.

Now, suppose that you are a leader of today's Russia or Poland. or Nigeria, or Mexico, or Brazil. And the banking authorities order you to murder your people with budget cuts and privatize everything so foreign financiers can loot you. They tell you that this free market insanity is what built the great Western powers. Well, The administrations just before Lincoln followed that policy. They took down the tariffs and manufacturing collapsed. Cotton grown by slaves became America's main product, sent to England to trade for goods we couldn't produce.

This got us weakness and bankruptcy so that even the Congress could not be paid. And when Lincoln was elected president on a contrary nationalist program, the British faction launched Civil War. Lincoln made America an industrial, agricultural, and military power, which his allies continued building after his murder.

The strong government action that made this possible was not socialism. It caused the greatest growth of private initiative and private property ever known. Tariffs on imported steel were raised to 50% and later to 90%, forcing into existence America's first steel mills. When the London-loving Wall Street bankers refused credit to the United States, the government printed lots of new green dollar bills, hired Philadelphia banker Jay Cook to sell government bonds to citizens, and passed federal usury laws limiting interest to 7%.

Lincoln armed the whole people, including the blacks, to defeat the slavery system left over from the British Empire, to defeat the British-backed rebellion in his southern territory. This problem may sound familiar to today's Mexicans, Sudanese, and Russians.

Lincoln organized the first railroad across the wilderness to the Pacific coast to be built at government expense under army supervision. Lincoln created millions of new private farms by his big giveaway program. Government land was given free to farm families. Cash and free land went to railroad builders, who got more construction money by selling the land to new farmers. Farm families were educated at government expense. Government scientists taught farmers about fertilizers, soil chemistry, and crop management. Farmers with cheap credit bought inexpensive machinery produced by patent-protected inventors who used inexpensive tariff-protected American steel. Diseases of livestock were conquered by government science and federal law.

In the colleges and the new agriculture department, Lincoln employed teachers trained by the great German biochemist, Justus von Liebig. Liebig taught these Americans that man at first sees everything around him bound in the chains of invariable fixed laws. Within himself alone, he recognizes a something which may govern these effects, a will which has the power to rule over all natural laws. The knowledge of nature forces upon us, said Liebig, the conviction that there exists an infinitely exalted being of whom we can only form some conception by the highest cultivation of every faculty of our minds.

Abraham Lincoln told farmers, a free people insists on universal education. “I know nothing so pleasant to the mind”, Lincoln said, “as the discovery of anything that is at once new and valuable, nothing that so lightens and sweetens toil as the hopeful pursuit of such discovery. For the educated mind, every blade of grass is a study, and to produce two where there was but one is both a profit and a pleasure.”

Lincoln said, “Population must increase rapidly, and the most valuable of all arts will be to get a comfortable subsistence from the smallest area of soil. No community whose every member possesses this art can ever be the victim of oppression in any of its forms. Such community will be alike independent of crowned kings, money kings, and land kings,” said Lincoln.

The British feared Lincoln as they had Franklin. The British press depicted him as a political extremist, a mad dog, a crackpot, and a loser. When Lincoln was killed, the US government convicted his assassins of a conspiracy with the secret intelligence agents in British Canada. That was the official verdict.

After the Civil War, the nationalists led by Henry Carey created new technologies which vastly expanded the power of man over nature in the US and overseas. The nationalist power centered in America's largest company, the Pennsylvania Railroad, a private enterprise built with Philadelphia city government money. Other railroads and steel and machine industries were all built by the same group of men. Their informal organization called the Philadelphia Interests overlapped with the federal government, the Army, and Navy, and science institutions that Franklin and his followers had set up.

They confidently invested huge sums in research and development without worrying about immediate profits, since their leader, Henry Carey, had designed the nation's strong protective tariff laws. Their banker, Jay Cooke, was still the government's private banker to keep national finance out of Wall Street and British control. By 1871 and 72, partner Andrew Carnegie was building the world's most advanced steel mill in Pittsburgh. They took control of the Union Pacific Railroad and started George Westinghouse's career by installing his air brake on the PRR trains. With government grants, Jay Cooke began construction of the huge Northern Pacific Railway.

When their Japanese friends set up a modern government, the Carey Group and the U.S. government sent over technical teams and anti-free trade economists for rapid Japanese development of science and technology. The nationalists planned a global system of railways, canals, and shipping. The American nationalists launched the industrialization of Japan, attempted it in China, and started it in Russia, whose czar, Alexander II, was a close ally of the martyred Lincoln. These nations could become powerfully independent. Standing together, they might overcome Britain's sabotage of their developments.

In 1871, the British created a new Philadelphia-based organization designed to smash the entire American political leadership. London banker Junius Morgan made a partnership of his son, J.P. Morgan, with Philadelphia's Drexel family, called at first Drexel Morgan, later simply J.P. Morgan and Company. The Drexels owned the Philadelphia Ledger, an editorial partner of the London Times. They ran a shameless worldwide slander campaign against Jay Cooke, warning that his depositors and lenders would lose everything, while the British squeezed his credit. They successfully bankrupted Cooke in 1873, setting off a panic that closed the stock exchange for a week and shut down American industry.

When the smoke cleared, Morgan and other British representative bankers had taken over US government finances. The Philadelphia interests had been broken and removed from their biggest projects, and the overall pace of American economy was never again recaptured.

J.P. Morgan, who sailed around in a yacht with a pirate flag, actually fancied himself the Jupiter of finance, the Roman name for the Greek god Zeus.

But the American Prometheus refused to give up. One of the Philadelphia partners was William J. Palmer, who had modernized the Pennsylvania Railroad and had won a Medal of Honor as a Civil War Cavalry General. General Palmer set up the Automatic Telegraph Company in 1870 to compete with Wall Street's Western Union. Palmer's assistant, Edward Johnson, hired for the company a brilliant 24-year-old inventor of telegraph devices named Thomas Alva Edison. Palmer set up Edison as an independent inventor, and Johnson remained Edison's business manager and closest friend from then on.

The Philadelphians' top scientist, Franklin Institute Research Chief George F. Parker, became Edison's science mentor and dear friend. The Philadelphians encouraged Edison as he perfected the telephone correcting the toy-like device of Alexander Graham Bell. When Edison invented sound recording, the phonograph, Barker and the cash-strapped Philadelphia group successfully schemed to make him famous. In 1878, Professor Barker gave Edison an intensive tutorial on the history of light and electricity and Barker asked Edison to make practical electric light his great project.

Edison soon announced that he was inventing the electric light, that he would advance civilization by giving mankind light and electric power. J.P. Morgan immediately swooped in and set up a Morgan-controlled Edison company that gave Edison a little helping of money in exchange for tight control. Edison mastered the necessary physics and chemistry and devised hundreds of inventions needed to begin public electric power.

Britain's pseudoscientists historically claimed that it was against well-known scientific laws to power many separate electric lights from the same power source.

The British and their whores in the press put out a stream of attacks calling Edison a fraud.

“Get your New York Times! Read all about it! Read all about it! Get your New York Times! Read all about it! Leaders of scientific community denounced the electric light as a failure. Edison is discredited. Get your New York Times! Read all about it! Edison's lab to be investigated for fraud. Get your New York Times! Read all about it! Get your New York Times!”

But Edison was a better thinker than the Newtonian fakers. Along with the thousands of experiments in his notebooks, there are working hypotheses on the nature of gravity as electromagnetism. Some depict the origin of the Earth's rotation in terms of the overlapping lines of force of the Sun and the Earth in the tradition of Johannes Kepler's work, a challenge to the Newtonian dogma that separates gravity from electromagnetism. Edison admired Bache's patron Alexander von Humboldt as the father of American science and kept Humboldt's bust in his laboratory.

Reggie: This is making me very uncomfortable, Tom. You know I've never sought the spotlight. I've always preferred to operate in the shadows, as it were. I think it's about time that I take a graceful exit. But don't worry about me. I'll be lurking somewhere. My thoughts have been around a very long time. We won't be far off.

Tom: I'm coming with you, Reggie.

When Edison's impossible light was proved, and his first US dynamo was successfully set up in New York, Morgan prohibited any more generators to be built. Edison and his friends had a stockholders revolt. And then they reached out to America's local governments, which put up the money to build power plants in their cities.

The Philadelphia nationalists made arrangements to build generators with Edison's partners in Germany France, Italy, Japan, Argentina, and many other countries. An apprentice named Frank Sprague worked with Edison on the first electric trains. Then the Philadelphians set up Sprague in business to build the first electric subways, streetcars, elevators, and electric tools.

Another Edison apprentice, Henry Ford, created America's automobile industry. Morgan changed the Edison Company name to General Electric and expelled Edison entirely. The railroads and all the great industries were seized by Wall Street and London financiers. But despite their plunder and destruction, the light of modern times had been turned on.

As patriots in each country today assess the wreckage caused by the ruling pirate economics, they worry about leaving this sinking ship for some unknown vessel. Yet real history teaches us that pirate empires are neither safe nor useful. and that mankind's power comes from the courage to aim for the stars.

Share this post