Why should we take a look back at what history we were taught? What does it matter? The Future needs to be shaped out of the present events. How can past events be of any use, other than what is already known. History may repeat itself if important lessons are not learnt, sure. But we have learnt our lessons, no? Great Britain is the motherland of democracy, which we know since the Magna Carta, no?

Well, Friedrich Schiller, according to an as yet unsourced quote by Sir Winston Churchill, was feared for his spirit. Why? Because he not only wrote beautiful poetry and drama, but also had a firm grip on how to make sense of what has been going on, as well as why that was the case.

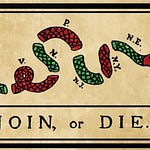

Following a few preliminary remarks by Schiller from his inaugural lecture as Professor of History at Jena University in 1789, I would recommend you make the time and watch the interview of Cynthia Chung on her recent paper which, as she expected, might seem outragous at first: How Britain had reconquered the U.S.A. and established an Anglo-American Empire.

Schiller writes:

“The course of studies which the scholar who feeds on bread alone sets himself, is very different from that of the philosophical mind. The former, who, for all his diligence, is interested merely in fulfilling the conditions under which he can perform a vocation and enjoy its advantages, who activates the powers of his mind only thereby to improve his material conditions and to satisfy a narrow-minded thirst for fame, (…). Who more holds up the progress of useful revolutions in the kingdom of knowledge than these very men? Every light radiated by a happy genius, in whichever science it be, makes their poverty apparent; their foils are bitterness, insidiousness, and desperation, for, in the school system they defend, they do battle at the same time for their entire existence. On that score, there is no more irreconcilable enemy, no more jealous official, no one more eager to denounce heresy than the bread-fed scholar.

How entirely differently the philosophical mind comports itself! As meticulously as the bread-fed scholar distinguishes his science from all others, the latter strives to extend the reach of his own, and to reestablish its bond with the others—reestablish, I say, for only the abstracting mind has set these boundaries, has sundered these sciences from one another. (…) New discoveries in the sphere of his activities, which cast the bread-fed scholar down, delight the philosophical mind. Perhaps they fill a gap which had still disfigured the growing whole of his conceptions, or they set the stone still missing in the edifice of his ideas, which then completes it. Even should these new discoveries leave it in ruins, a new chain of thoughts, a new natural phenomenon, a newly discovered law in the material world overthrow the entire edifice of his science, no matter: He has always loved truth more than his system, and he will gladly exchange the old, insufficient form for a new one, more beautiful. Indeed, if no blow from the outside shatters his edifice of ideas, he himself will be the first to tear it apart, discontented, to reestablish it more perfected. Through always new and more beautiful forms of thought, the philosophical mind strides forth to higher excellence, while the bread-fed scholar, in eternal stagnation of mind, guards over the barren monotony of his school-conceptions.”

(…)

“Out of the entire sum of these events, the universal historian selects those which have had an essential, irrefutable, and easily ascertainable influence upon the contemporary form of the world, and on the conditions of the generations now living. It is the relationship of an historical fact to the present constitution of the world, therefore, which must be seen in order to assemble material for world history. World history thus proceeds from a principle, which is exactly contrary to the beginning of the world. The real succession of events descends from the origin of objects down to their most recent ordering; the universal historian ascends from the most recent world situation, upwards toward the origin of things. When he ascends from the current year and century in thoughts to the next preceding, and takes note of those among the events presented to him containing the explanation for the succeeding years and centuries, when he has continued this process stepwise up to the beginning —not of the world, for to that place there is no guide—but to the beginning of the monuments, then he decides to retrace his steps on the path thus prepared, and to descend, unhindered and with light steps, with the guide of those noted facts, from the beginning of the monuments down to the most recent age. That is the universal history we have, and which will be presented to you.” (…)

Now, if you apply what Schiller laid out in theory to a review of historical evidence for the United States of America from 1776 to the present, you may find yourself in agreement with Cynthia Chung. Enjoy her presentation!

Articles discussed:

The Difference Between William McKinley’s American System School of Protective Tariffs and Today

Sugar and Spice and Everything Vice: The Empire’s Sin City City of London

The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass

Books discussed:

Clash of the Two Americas, Vol. 1-4, by Matt Ehret

Treason in America, by Anton Chaitkin

The Empire on which the Black Sun Never Set, by Cynthia Chung

Videos discussed:

1932: A True History of the U.S. — "We Must Speak not of parties, but of universal principles..."

Bandung (Asian-African) Conference- The Voice of the People, RTF-Lecture by Cynthia Chung

Teddy Roosevelt and American Imperialism, Part 1, RTF Lecture by Magdalena Therrien

Teddy Roosevelt and American Imperialism, Part 2, RTF-Lecture by Magdalena Therrien

Cynthia Chung Websites:

Share this post