The Reason why CJ Hopkins should be safe - and why the Berlin Prosecutor's targeting is even more outrageous

Germany's Federal Court of Justice ruled back in 1973 that Nazi Symbols can be used in efforts to warn against a recurrence. Why then are they targeting Hopkins in Berlin?

The instrumentalization of legal provisions on National Socialism against critics of the totalitarian measures in the context of the Corona crisis continues. After the charges of incitement of the people against Sucharit Bhakdi and Robert Hoeschele as well as a corresponding investigation against Monica Felgendreher (because she had quoted a speech of Vera Sharav), and after the complaint against Holocaust survivor Vera Sharav herself, now the author and artist CJ Hopkins has come into the crosshairs of the public prosecutor's office in Berlin. He is accused of violating paragraphs 86 and 86a and of spreading Nazi symbols for the purpose of propaganda when he posted a tweet about his book “The Rise of the New Normal Reich,” which is banned in Germany.

One would have to laugh at such shenanigans (meaning the actions of the judiciary) if the background were not so serious - the instrumentalization of the law against criticism of government policies to avert a purported danger and to enforce a purported solution. For to invoke penal provisions created to deter trivialization of Nazi injustice and rule in such cases that clearly originate in an intention to stop the emergence of totalitarianism (as in Hopkins case) and/or to warn against possible genocide (like neveragainisnowglobal.com) is a huge red flag.

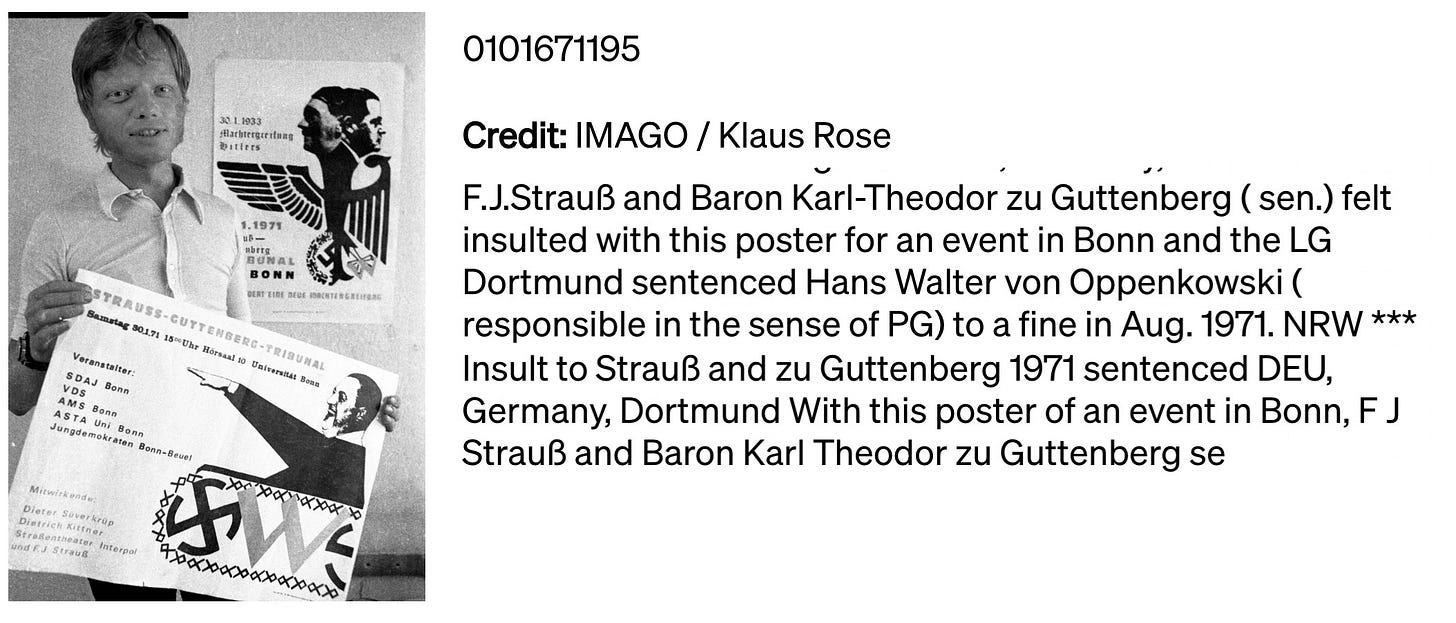

In the case of CJ Hopkins, however, it should not be assumed that the Berlin public prosecutors will get far with their plan (like all public prosecutors' offices in Germany, the Berlin prosecutors are subject to instructions from their higher-ups, and are thus politically dependent, since the justice ministers of the Länder can instruct the general public prosecutors' offices). But a fundamental ruling of the Federal Court of Justice of February 14, 1973 is unmbiguous [Ref.: 3 StR 3/72 I]. The case then dealt with the graphic representation of a warning against the “seizure of power” by former German Defence Minister and Prime Minister of Bavaria, Franz-Josef Strauß (FJS), and Karl Theodor Freiherr von und zu Guttenberg sen. (the Grandfather of present-day “KT” who was forced to resign over plagiarism in his doctoral thesis), which the ASTA of Bonn University, together with the marxist-leninist youth organisation SDAJ, wanted to warn others (by using Nazi symbols and by means of a “tribunal”) on January 30, 1971 about a “power-grab” of FJS and KT, sen.

However, the Federal Supreme Court rejected the prosecution's appeal against the acquittal of a responsible organizer of the “tribunal” in said landmark judgment two years later. The Senate recognized that Section 86a of the German Criminal Code (now also invoked against Hopkins) “insofar as it refers to isignia of a former National Socialist organization, intends to ban these symbols and their reproduction, but not the designated remembrance, from certain types of use and from dissemination in the Federal Republic of Germany.” The “remembrance” - i.e. the comparison, or matching with current events, for the purpose of prevention - was explicitly permitted by that interpretation of the highest court.

The BGH thus made it clear as early as 1973 that Nazi or other anti-constitutional symbols, if used “in a certain way,” may not be restricted in their dissemination. At that time, the symbols, the swastika and the Reich eagle with swastika, had been used in a cut and graphically processed manner, so that in the opinion of the BGH “... already it could not be beyond doubt” whether this was to be regarded at all as a sign of a former National Socialist organization in the sense of § 86 a Criminal Code. But even if it were. It would not matter at all, according to the BGH, because it was obvious that the symbols were used in a way that was unambiguous,

“(...) because the defendant's actions do not fulfill the designated element of the crime for the very reason that, according to the entire content (...) an effect on third parties in a direction corresponding to the symbolic content of National Socialist symbols cannot emanate (...) and because their dissemination also otherwise does not recognizably run counter to the protective purpose of § 86 a StGB.”

The purpose of the images at the time was a warning against a potential new “power-grab”.

“The attitude sharply rejecting National Socialism is (...) quite obviously the advertising basis characterizing both the author's point of view and that of the audience expected by him on whom the [works] are intended to have an effect.”

CJ Hopkins has also hardly left any doubt with his book that all he wants is to avert the emergence of a new totalitarianism in the manner of the Nazis (albeit different). In such cases, according to the BGH in 1973 on the basis of the case then at that time, it is already recognizable without further ado according to their content, i.e. regardless of the external context of the use of the symbols, “that insofar as the memory of National Socialism is thereby evoked, this is done in an emphatically rejecting sense. The attitude sharply rejecting National Socialism is (...) quite obviously the advertising basis which characterizes both the point of view of the author and that of the audience expected by him on whom the [works] are to have an effect."

Works with such content are “far from being suitable to serve a revival of National Socialist ideas or even former National Socialist organizations,” the BGH held in a supreme court decision.

“For persons with neo-Nazi objectives would never want to use the marks of National Socialist organizations in a pictorial composition expressing their rejection.”

Thus, neo-Nazis could not invoke such a type of use to derive from it a justification for use in the public.

“Similarly, in a reproduction of the insignia in pejorative distortion, such persons will see in a reproduction in the pictorial context chosen here and commenting on the depiction in writing at most a mockery of the insignia ‘sacred’ to them.”

So the question that the Berlin judiciary should have asked itself here before taking up the investigation against CJ Hopkins is clearly: would neo-Nazis print swastikas on disposable items such as facemasks, which in their use contaminate and sully their, according to the BGH, “sacred” symbol with moisture from breathing and dirt from their trouser pockets? Clearly no! So from this alone it had to be clear to every jurist that the way of use in CJ Hopkins’s case was and is completely uncritical in the sense of § 86a of the German Criminal Code.

In this respect, this is where the true scandal reveals itself: legally with little or no validity, presumably highly politically motivated, the approach of the Berlin public prosecutor's office against a prominent critic is harsh deterrence. They must be wanting to nip in the bud the fundamental justification of warnings against the slide into a new totalitarianism. Much like the warnings of Holocaust survivors, based on the moral foundation of early warners like Primo Levi (“It happened, therefore it can happen again”) and the U.S. President's Commission on the Holocaust (“Not only has the moral landscape of human reality been altered by the Holocaust, but the acceleration of technology (…) now threaten human existence itself”), the warnings of critics such as CJ Hopkins about the emergence of a totalitarian society are, in their own way, more than justified.

Those who wish to be outraged and dismiss such warnings as inappropriate must be reminded that it is in the nature of any warning to express a concern in order to prevent it from becoming a reality. However, those who want to silence the sirens are preventing the firefighters from even having a chance to put out the fire in time. It may be that the fire department goes out for nothing. But to prevent them from going out, to delegitimize social debates, is indecent. Warnings are not!